We are losing our indigenous communities, such as the Hadzabe, globally as time passes. Pressure from the outside world for their land and resources has them at the tipping point of survival. From the top of our Arctic, across America, inside the Amazon, across the South Pacific, and inside of Africa, so many of these communities are disappearing. I have been fortunate to have been invited to many of these communities over the years. On each occasion, I am taken aback by their generosity and willingness to educate me on their way of life. With each passing day, our modern societies become reliant on technology. Just this summer, Instagram and Facebook went down for a few hours, and you would think the world was ending.

Automation and artificial intelligence continually replace human jobs in hundreds of industries. Progress is inevitable. This progress has led to advances our ancestors only thought of as science fiction. We should continue celebrating these advances and not lose sight of where we came from or who we are as a species. We need not lose sight of the fact we share this planet with billions of other people and countless species. Indigenous societies have the same rights to our world as we do. Often, people feel sorry for them. But why? My feelings are never sorrowful, often quite the opposite. I admire their way of life, their ability to make a strong connection with the Earth, and how much they care for the planet. I leave feeling sorry for our modern society’s many obsessions with things that provide short-term happiness. Wealth has many metrics to be measured.

One particular indigenous society made a substantial impact on me. The Hadzabe. And they need our help.

Meeting the Hadzabe Tribe

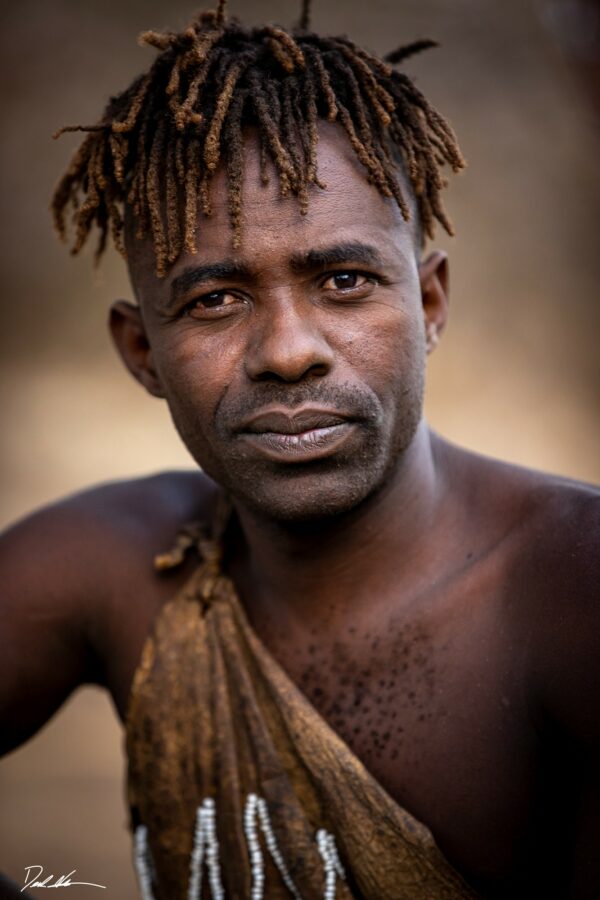

(Limited Edition Fine Art Print of 10 – Chief – Derek Nielsen Photography)

The Journey To The Hadzabe Camp Location

Recently, my journies pulled me back to East Africa. A place still wild and free. Unique and beautiful because wild animals still outnumber humans. Inside this region, particularly inside Tanzania, lives a tribe practicing a way of life our species has been practicing for thousands of years, the Hadzabe. Like so many indigenous tribes worldwide, the Hadzabe face pressure to conform to modern society. Their sacred lands and hunting grounds are increasingly contracting. However, despite this pressure, the Hadzabe have held on to their traditions and intend to keep them this way.

Located in the district of Karatu around Lake Eyasi, I first met one of the tribal camps in 2021. With me, my long-time friend and native Tanzanian Steven Ngowi, and two women. We left our lodge earlier than usual to be at the tribal camp in time to witness the morning hunt. Because wildlife activity is flourishing in the morning hours, we set out early. The road in is long, dusty, and bumpy. Part of you questions your choices about doing this all together. Particularly if you have a slight hangover like the 4 of us shared this morning.

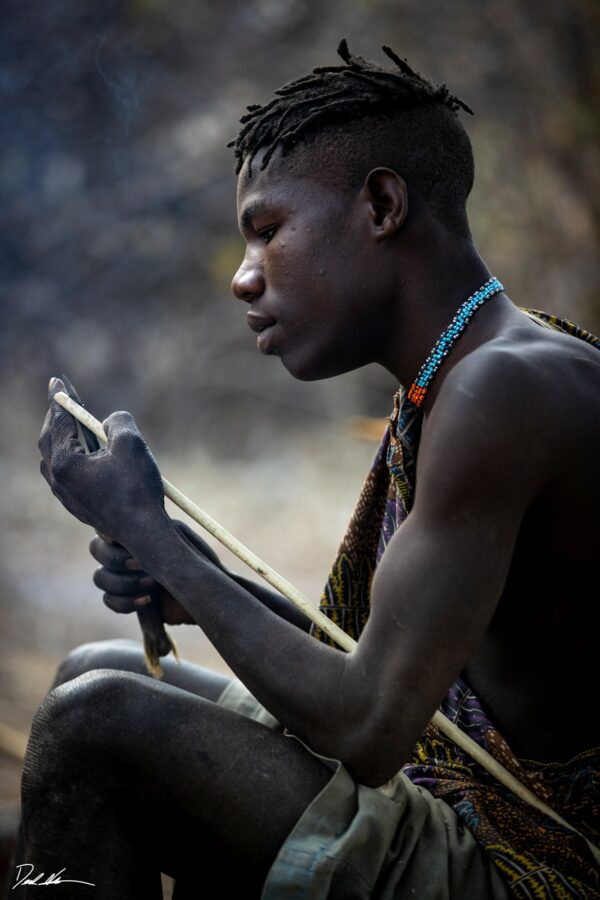

(Limited Edition Fine Art Print of 10 – The Hunt – Derek Nielsen Photography)

Different from many of the roadside National Park entrance tourist-exposed tribes, the Hadzabe take a commitment to go and visit. Every bit of it is worth it. Along the drive in, we picked up our translator, Alex Puwale. Our soon-to-be host speaks Hadzane, a complex language for me, as it uses click and popping sounds with the tongue. Alex grew up with the Hadzabe as neighbors. He originates from the Iraqw Tribe. Without Alex, the experience would not be possible. Our car rolled along this dark and dusty road veering off the road onto an even smaller, less groomed path. We had to be close. Splitting the welcoming committee of neighboring farm’s goats, we rocked our way back and forth across what seemed to be a dried riverbed until we found the camp entrance.

Initial Introduction

The air was still cold. My body shivering. Mornings take a while to heat up because so much ground heat is lost overnight in this dry climate this time of year. Still recovering from the drive-in, I could smell the wood smoke from the camp’s fires passing through the bush. This was the first time in my photography career that I was exclusively visiting a tribe for the purpose of capturing beautiful images. This excitement became my demise. When we first entered the camp, a small circle of men sat around a slow-burning fire. Immediately, my creative mind took over searching for compositions. In any normal situation, I would introduce myself, let the members of any group I was visiting do the same, and then eventually begin taking photos. I was so excited I started snapping photos right away. Rightly so, the men were not impressed with my presence. After only a few moments, I realized the mistake I had made.

Like a dog putting its tail between its legs, I put my cameras away, sitting beside two men around the fire. Graciously, they let me in, and I knew I had to find a way back into the group’s favor. One of the men was packing what looked to be a small stone pipe with a tobacco mixture. I don’t like to smoke, but I figured I could try it to show I was interested in participating. He lit the pipe and then passed it in my direction. I took a moderate puff, inhaled without choking, thankfully, and passed it on. From what I could tell, I was back in their good graces.

A few moments passed filled with awkward charades-like communication when one of the group members spotted a small bird in a nearby tree. It took flight, and he grabbed his bow and arrow in one motion, fired, and knocked the little bird out of the sky. I could not believe the accuracy. He walked over, picked up the dead bird, and placed it directly in the fire. He sat next to me, and from what I could tell, he was going to offer it, or some of it, to me. Sure enough, he pulled it from the fire, pulled off its head, and offered it to me. So many thoughts raced through my head. I would undoubtedly offend him if I declined his offer, but the risk of contracting an illness was high. Ebola, bird flu, the next covid 19. All of these potentially originated from eating bush meat. I graciously declined and knew I was back in the dog house.

Moments later, the group chief spotted another bird, took one shot, and had another ready for the fire. He sat down next to me on the same log as the new bird cooked, and all I could think about was how badly I didn’t want to disrespect this man. I would assume 99.9% of his outside guests don’t eat the bush meat offered, but I desperately wanted to show the group I was sincere. He reached his hand down to pull the cooking bird off the fire, and I gestured to him to let it continue to cook. A smile grew on his face. My exact thought was that if I let it cook long enough, whatever was inside would be sterilized. He reached in, pulled the head off, and offered it to me. I stood up, popped it in, and down it went. Sparing the details of how it tasted or any of the textures, at that moment, I was accepted. I picked up my camera and composed several strong images of the tribe’s members. There are a lot of risks involved with eating bush meat, and I certainly don’t recommend anyone following my lead, but there are certain moments in life when we have to gamble a little.

Portraits of the Hadzabe

Once I made up for my overanxious mistake, I picked my cameras back up. This was when the photography magic happened. I worked my way around the group, evaluating the light. Now, I was one of them. Every tribal member’s body language changed. I aimed to capture their personalities while simultaneously shining a light on their way of life. I moved from member to member with my Canon R5 equipped with my favorite lens for this type of work, RF 70-200 F2.8 L IS USM. This lens provides me with the creative range necessary to be an observer while giving me an incredible depth of field. No, I am not a Canon Ambassador. Yet.

We were to be heading out on a hunt shortly. The designated hunting group for this morning was one by one sharpening their arrows, checking them for imperfections from top to bottom. When the strength of the tribe relies on the success of the hunt, little room for error is accepted. Off we went. Breakfast was out climbing in the bush.

Hunting with the bushmen

As an animal lover, I knew the hunt would be brutal to watch, but I also knew it was a necessity for the tribe to survive. The Hadzabe only hunt for each meal, and nothing goes to waste. Their sustainable existence is a model for the rest of the world to achieve. Four hunters, including the chief, led me deep into the bush. We were looking for anything that moved.

A few small birds scattered into a thorny tree. The men drew arrows, crouching for the perfect shot. Without hesitation, the second in position hit his target, knocking one of the birds to the ground. He picked it up, ensured it was dead, then tied it to his belt. Several others met the same fate as the men worked in and out of the dense dried brush. I was in awe of their accuracy and compassion for the animals they hunted. Each checked the fallen animal before adding it to the bounty.

We were in the bush for around an hour before they had enough to share with the tribe back at camp. Every edible part of the birds was consumed, and what was left fed the hunting dogs. I thanked the chief for the opportunity. While not common, there are potentially dangerous animals in the bush. He kept a watchful eye out for me and my safety.

Recently, I have been made aware that other visitors asked to participate actively in hunting with these tribal members. Please, when visiting, leave the hunting to the tribal members. We are only to be observers. What they do is not a sport, and it is not a game. Do not exploit them or take advantage of their hospitality. Their way of life is constantly being threatened; don’t be the reason they are forced to assimilate into modern society.

Returning as a friend.

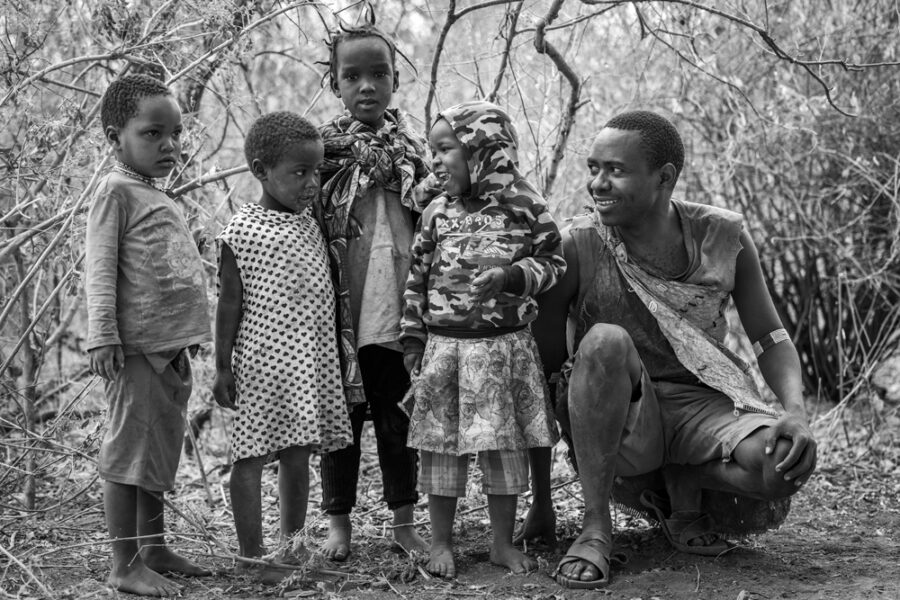

Recently, I returned to the same Hadzabe tribe as my first trip described above, but this time with my family. I wanted them to meet the members who were so kind to me in my previous experience. Show them the men and women who taught me serval valuable lessons that day. Most of the members were still part of the same camp. I can only imagine many visitors come through never to return. My eyes locked with the chiefs. He lit up with enthusiasm, remembering my visit only a year prior. This time, instead of quickly snapping images, I pulled out my phone to show him the edited photos taken during the previous trip, highlighting not only his masculine beauty but also the vibrant beauty of his people. I couldn’t hide my smile as he quickly grabbed my phone, running from member to member to show them how they looked.

My family quickly engaged with the members sitting around the morning fire. This time I only sat back and watched. I didn’t take a single photo until I had soaked in the entire experience fully present. Compositions missed from my last visit lingered in my mind for a whole year. I grabbed my same camera, dressed with my favorite setup, and, like many of the greats before me, composed image after image as if each were the last photo I was ever going to take.

Preserving the Hadzabe way of life

As a child, I read about indigenous people around the world in publications like National Geographic and various encyclopedias. Back then, they seemed almost fictitious. I could not comprehend a way of life where water did not flow freely out of a tap or had to worry about where my next meal came from or when it would be. I am undoubtedly from a society with plentiful resources full of boundless opportunity. Some may say privileged. I can’t even argue. But I have learned over the years of traveling that every society is entitled to its own way of life—its own way of existing as long as it doesn’t impede on others.

The Hadzabe are no different. They are entitled to live as they have for hundreds if not thousands of years. Only recently has the planet’s growing population threatened their hunting grounds while climate change is simultaneously impacting their ecosystem? Until recently, I did not know of this tribe. Now, because of how much I have learned from them, I don’t want to imagine a world without them living THEIR way of life. Not ours.

As fellow inhabitants of this planet, we must stand up for our indigenous communities. They cast a near-invisible footprint environmentally on this planet. We do not. Made famous by the “Spider-Man” comics, although these sentiments reverberate throughout history, “With Great Power, Comes Great Responsibility.” Encourage government officials to do the right thing. Protecting their lands is the least we can do. Decreasing our own impact on the environment can and will help down the road. And when allowed, visiting these communities helps shape our perspectives. Sometimes, a perspective shift is precisely what we need to remember what is important in life. My time with the Hadzabe has undeniably made me a better human, and I am grateful for that.

For more information on how to visit the Hadzabe, contact Ndifo Safari to learn more or book your own adventure. To learn more about my conservation work or how to plan your own safari, please check out more of my articles. If you have enjoyed the photography in this article, please visit our gallery for a more comprehensive selection of luxury fine art photography. Any images in the article will be sold to help support the Global Philanthropy Alliance to help develop young social entrepreneurs in Africa.

Hello! I'm Derek.

DEREK NIELSEN PHOTOGRAPHY RAISES AWARENESS ABOUT THE GLOBAL NEED FOR CONSERVATION THROUGH PHOTOGRAPHY AND DONATES UP TO 15% OF ALL SALES BACK TO ENVIRONMENTAL ORGANIZATIONS AROUND THE WORLD.